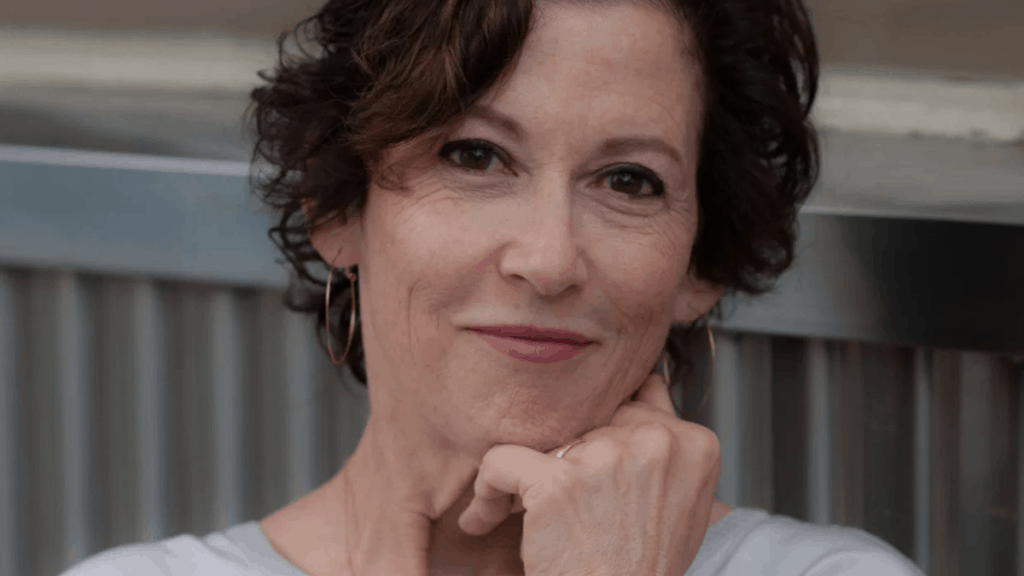

Interview with Abigail Enelow Myers, MN, ARNP

Abby Enelow Myers, MN, ARNP, based in Seattle, has been in practice for 23 years. PS-WA talked with her about the latest perinatal mood and anxiety disorder (PMAD) trends she has seen in her practice, approaching the idea of medication with families who may be wary about it, and the stigma around the use of medication and of PMADs in general.

Myers said a good encapsulation of her thinking is found in this post by Lee S. Cohen, who is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. It is found on the Women’s Mental Health website. It outlines clinical scenarios where there are inconsistencies between clinical practice and the evidence. Cohen lists these key discrepancies:

- Using lower doses of antidepressants during pregnancy. Studies show that the dose that “gets them well is typically the dose that keeps them well.”

- Switching to sertraline in pregnancy/postpartum. If a patient is doing well on another antidepressant and switches to sertraline or another medication, this may put her at risk of recurrence.

- Changing to a Category B label drug.

- Discontinuing lithium during pregnancy. This is risky, and results in high rate of relapse.

- Trying alternative therapies. There is frequent relapse when combined with stopping (effective) antidepressants.

- Stopping breastfeeding or deferring antidepressants.

- Using non-benzodiazepine sedative-hypnotics.

- Pumping and dumping

- Failing to bring up contraception.

A big trend that Myers sees is increasing recognition that patients have anxiety, depression, or both during pregnancy, not just postpartum. Providers are beginning to recognize this and to become more knowledgeable about the issue and the safety profiles of medication usage. Some patients report that because they know they have a history of depression and/or anxiety, that this may put them at risk for a perinatal mood disorder. Some women will therefore come in before they get pregnant, she says. Women may also report that their own mothers had unrecognized postpartum depression, which increases their concern about their own risk. Pregnancy is a very fragile time, and Myers says if the patient recognizes that they may be at risk for a PMAD, they are well ahead of the game in terms of prevention.

The stigma around perinatal mood and anxiety disorders continues to occur despite increasing public awareness. Women may be especially reluctant to share their symptoms while pregnant, Myers reports. With this shame, often patients don’t want to share with their provider, and if the provider does not ask, the chances for prevention won’t occur.

However, across her years of clinical work, Myers sees a decrease in the stigma of taking medication. There are multiple factors for why this may be, some of which include increased media attention, celebrities sharing that medication helped their recovery, and the increase in women sharing their own experiences. In addition there has been a massive increase in research on the safety of medications during both pregnancy and breastfeeding.

It is critical to get moms to meet up with other moms who may share their experiences with treatment– both counseling and medication. Most of the time, Myers reports that by the time a woman comes in to see her, their distress is such that they just want relief, and so medication is on the table for them.

If a patient is wary of taking medication during pregnancy or postpartum, Myers frames the issue differently, stressing that this is a physiological problem, that neurochemicals are off. She starts by just listening to the mother’s report of her experience. She then determines whether supportive counseling is enough. To determine this objectively, she uses the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale, a validated screening tool (PDSS). She finds that this scale is more informative than the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression scale (EDPS) because it gives much more detailed information and helps to determine the severity of the problem. The score can aid in determining whether medications are recommended. She states that often simply sharing the score with the mom will influence her acceptance and willingness to try medication.

As far as approach to treatment, if a patient is pregnant and had been on meds before the pregnancy, Myers will prescribe the lowest dose that is effective, especially in the first trimester of pregnancy, and then watches for any return of symptoms. If the patient does well, she will continue to watch for symptoms returning in the second and third trimesters and increase if needed. But in all cases she recommends increasing the dose a few weeks before delivery to prevent a relapse in the postpartum time period.

If a patient’s decision is to stay off meds, Myers really emphasizes using all the support that’s available: more help, sleep, support groups, and other networks. She emphasizes that sleep is critically important, and she stresses that patients work on finding a way for the amount of sleep to be maximized. She cites the important standard of getting 5 hours of uninterrupted sleep. Hopefully, she states, the partner will share “shifts” of these blocks of sleep. Although expensive, nighttime doulas can also be an option to help ensure sleep for mom. Extended family may be willing to help defray costs.

One new article of interest for Myers describes the low incidence of PMADs in mothers with no prior psychiatric history. But Myers wonders that if you dig deeper into the woman’s background, there may indeed have been some unrecognized psychiatric history, such as chronic low grade depression known as “dysthymia.”

Finally, Myers is seeing more and more women struggling with depression related to infertility. Issues such as miscarriage, fertility treatments, and decisions after failure of treatments have a profound effect on a woman and her partner. The grief and loss that inevitably follow must be addressed.